GovInfo Day is an annual day long symposium focusing on government, legal and data related information for librarians and library staff. Since its inception in the late 1990s, GovInfo Day (formerly known as the Annual Gathering for Librarians Interested in Government and Legal Information) has expanded from an annual half day workshop into a daylong event attracting national interest with both speakers and attendees coming from across Canada.

Sponsored by Simon Fraser University Library and the British Columbia Library Association’s Information Policy Committee GovInfo Day 2015 featured topics on changes to the way the Government of Canada is disseminating information, ways we can capture and archive government information, access to Canada’s archival record and resources for personal planning and Representation Agreements

Open Government at the GC: – creating a “virtual library” presented by Patrick McDermott, Senior Manager, Open Government Systems, Chief Information Officer Branch, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat / Government of Canada.

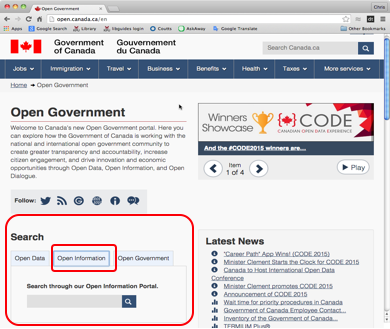

Via teleconference, McDermott described the Government of Canada’s (GC), Virtual Library (VL, also called “Open Information Portal”) which is one part of GC’s second Action Plan on Open Government, 2014 – 2016[1] to make federal government information more openly accessible. The plan was developed through a consultative process and is being overseen by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS). The goal of the VL is to simplify public access to open information from the federal government. “Open Information”, refers to all sorts of unstructured resources (such as publications, presentations, consultants’ reports, ATI summaries, videos, etc.) in contrast to ‘Open Data’, which are structured, machine-readable files. (Open Data is another prong of the action plan.)

In phase one of the Virtual Library, TBS has combined metadata from two existing repositories of full-text government resources: Government of Canada Publications and Library and Archives Canada (LAC). The resulting beta Virtual Library is accessed through a single search box, available on GC’s Open Government site at open.canada.ca. Right now, it supplements these two existing repositories which continue to exist and have their own search interfaces. The next phase of development will add other existing “information assets” held by departments, as well as new assets. In the longer-term, GC sees the Virtual Library being federated with other Canadian and international government agencies.

There was lively discussion and many questions from the audience, briefly summarized here:

Q: Why build the Virtual Library instead of developing a better search engine for existing collections?

A: The move to a single metadata search anticipates fundamental changes in the structure of the federal government’s website which will not be organized primarily by department.

Q: The term ‘Library’ implies services, not just collections. What services will the VL include in order to help the public effectively locate and use the VL, including data literacy?

A: Another department — Employment and Social Development Canada — is developing an action plan to build digital literacy. It will rely heavily on private, non-profit and academic organizations to implement.

Q: How can TBS effectively collect and make searchable such a wide range of formats through a single search?

A. McDermott acknowledged that it’s very challenging. They will be relying on metadata to help users filter their results. They will also strive to standardize formats, but this is not easy. There is concern about the long-term readability of files.

Q: How will “new assets” be identified and added?

A: GC has issued a new directive mandating that all government information be “open by default”, with exceptions when there are ownership, security, privacy, and/or confidentiality concerns.[2] This is a big culture shift for some areas. TBS is developing an inventory process. [An audience member suggested bringing more government agencies under the mandatory submission requirements of the Financial Administration Act.[3]

Q: National security is cited as a cause for exclusion from the VL. Who makes the decision about what will not be added to the VL, and will this process be transparent?

A: The government agency that produced the asset is its custodian and makes the decision of whether to deposit it in the VL. This issue is currently being discussed among senior managers.

Q: How will the long-term availability of resources in the VL be assured?

A: This is still being decided. McDermott initially said that the plan is to save everything listed in the VL metadata catalogue through some form of file sharing, though not everything would be easily available online after a certain period. GC is concerned that this will create a very large “digital footprint” which would be too costly to maintain. When questioned more closely, though, it seemed that some resources would not be permanently saved. McDermott noted that material may be selected by LAC for permanent retention based on anticipated business and heritage value. He also noted that the “custodial department” which created a resource in the VL (e.g. Health Canada) may have a say in whether it is held for the long-term.

There was heated discussion on this point and the audience strongly voiced the view that all of the works should be permanently saved because we know that it is impossible to fully anticipate future needs or the potential value in many works. There would also be a great risk of political pressure influencing retention decisions. Much has already been lost through the recent re-design of the federal government’s website and closure of departmental libraries. One attendee gave a recent example of a person researching aboriginal consultation in fisheries planning who needed documents from hearings held in BC 40 years ago by the [then] Dept. of Fisheries. No government agency had them, including Fisheries & Oceans, and Library and Archives Canada. The DFO Library, which would likely have held the documents, was recently closed and many documents destroyed. By sheer luck, the researcher tracked down a person who had attended the hearings and kept the documents.

Q: Why is the Treasury Board in charge of the VL?

A: TBS doesn’t plan to host the VL in perpetuity. It fits right now in TBS because of the policy driving its creation which requires a systemic change toward a more open culture in the federal government. Patrick sees this culture shift as the greatest challenge.

Q: The VL is part of a policy initiative by the current government. What happens if the policy direction behind it changes? What is the long-term plan to ensure perpetual access when there is currently no enabling legislation, and it does not appear to be seen [by some] as part of LAC’s mandate?

A: McDermott acknowledges the risk, as with any program. They’re building the VL to be ‘portable’ to a permanent home.

Q: Will there be a formal consultation process with librarians and archivists through existing networks to tap into our expertise?

A: TBS will be attending two major conferences in Ottawa this spring: CLA and the Congress of the Social Sciences and Humanities. Patrick welcomes names of suggested groups to consult. Comments can be posted on the Action Plan on Open Government website (strongly encouraged) or sent by email. Carla Graebner will be posting list of key persons to contact with feedback on the GOVINFO listserv. She has also offered to collate responses from those who wish to remain anonymous; send these to Carla at: [email protected]. [Note: CLA’s response to Virtual Library proposal is appended below.]

Q re: Open Data: Will the inventory of departmental data holdings be made publicly available regardless of whether the data itself can be released?

- No guarantee; this is under discussion.

Canadian Library Association’s response to Virtual Library proposal:

“Open Docs” Virtual Library: In regards to the “Open Docs” Virtual Library that is proposed as part of the current Action Plan on Open Government, the CLA strongly recommends that broad, external consultation on the initiative be undertaken and that the long-term preservation and accessibility of existing and forthcoming publications be ensured. It is recommended that the government develop a clear strategy for the digitization and preservation of historical government documents, to support free, online access to publications through the “Open Docs” Virtual Library. Preservation of digitized and born digital materials made accessible through the “Open Docs” Virtual Library is essential to supporting government accountability and openness. Given the easily changeable nature of digital content, the government should ensure that when updates or changes to documents are made, previous versions are not removed from the web. Original documents represent the historical record of government policy and activity and should therefore not be removed. Finally, concrete measures should be taken to address the digital divide that exists in Canada that may hinder the ability of Canadians to access online government information made available through the “Open Docs” Virtual Library. There is mention of funding and tools for Canadians’ digital literacy tools which is something CLA has advocated for. We are encouraged and are keen to see the details of this suggestion unfold.

Excerpted from CLA submission to the Action Plan on Open Government 2.0 Consultation October 20, 2014

— Chris Burns

Unified Access to Collections and Trustworthy Digital Repository Services: Canadiana’s New Digital Preservation and Access Infrastructure presented by William Wueppelmann, CIO, Canadiana.org.

William Wueppelmann, CIO of Canadiana.org, spoke about trustworthy digital preservation and access. He gave a history of Canadiana’s activity starting back in 1978 as a microfilming program that eventually converted to a digitizing program. Five years ago the old platform was no longer viable and merged with Alouette necessitating changes and the development of a new platform. The merger created a national metadata inventory of their existing digital collections of not just libraries but archives and museums, too. Currently Canadiana has 31 million pages of content and is projected to double by 2016 with managing content for other institutions. The collection includes the Library of Parliament’s debates (from both houses), speeches and statements from the Department of Foreign Affairs from 1945-1994 and will eventually include parliamentary journals. For more information: http://www.canadiana.ca/en/heritage-project

There are three basic parts to the Canadiana platform: trustworthy digital repository (TDR), Linked Open Data, and Canadiana Online. The TDR certification process is set by the Council of Research Libraries (CRL) and includes digital object management, organizational infrastructure, technologies, technical infrastructure, and security. There are five certified TDRs in North America and only one in Canada – Scholars Portal digital journals; Canadiana hopes to be the 2nd.

Wueppelmann reviewed the TDR architecture: there are a minimum of five copies required which must be geographically distributed in three locations: Ottawa, U of T, U of A and a commercial operation in Montreal. Each Submission Information Package (SIP) and Archival Information Package (AIP) are packaged as BagIt archives (hierarchical file packaging format designed to support disk-based storage and network transfer of arbitrary digital content.[4]) The goal is to be as transparent as possible by providing policy control standards, ensuring that preservation agreements are made with all donors, and indicating how the content is accessed. Further details are available from http://www.canadiana.ca/en/trustworthy-digital-repository

Finally, Wueppelmann reviewed Canadiana’s succession planning: if for some reason Canadiana.org couldn’t fulfill its mandate, those institutions identified in the succession plan would continue on with the TDR. Canadiana has an agreement in principle with the UofT, UofA, BAnQ, and LAC to form a mutual backup network, and has copies onsite at LAC and UofT, soon the UofA. Canadiana Online is the next generation platform, which will have the ability to add metadata at a later time, and will aggregate all content into one place which will be searchable. Consultation with librarians and archivists undertaken last year and produced a white paper: https://drive.google.com/a/c7a.ca/file/d/0B_U2mpVyAi45Sld0YTNKZ3pmN3c/view

— Mary-Anne McDougall

Resources from Nidus: Planning for supported decision making, incapacity, and end-of-life care presented by Joanne Taylor, Executive Director and Registrar, Nidus Personal Planning Resource Centre and Registry.

Joanne Taylor, Executive Director and Registrar of the Nidus Personal Planning Resource Centre and Registry spoke about the history and mandate of the Centre. This non-profit, charitable organization provides British Columbia adult residents with expertise on Representation Agreements, with education and facilitation related to personal planning, and with a registry for personal planning documents.

Nidus evolved as a process, which importantly included the passage of the Representation Agreement Act in 1993[5]. This legislation is unique to BC and is celebrated for supporting personal decision making over guardianship. Sections 7 and 9 of the Act cover the authorities that can be included in a Representation Agreement.

Section 7 is designed to provide standard powers to one or more trusted persons when an adult, who cannot manage his or her affairs or make decisions independently, needs help today with health care, personal care, legal affairs, and routine management of financial affairs. Section 7 provides a legal alternative to adult guardianship.

Section 9 allows adults to plan for the future in case they need assistance making health care and/or personal care decisions due to illness, injury or disability. Section 9 allows the assignment of broader or non-standard authorities (such as refusing life-support) and may only be used by someone capable of understanding the content of the document and the role of the representative. A Section 9 Representative Agreement does not cover financial and legal affairs, for which a separate legal document is required (either an Enduring Power of Attorney or a Representative Agreement with Section 7 routine finances).

The Nidus web site at http://www.nidus.ca includes the forms and support necessary to complete and to register a Representation Agreement. The Centre also offers training, and its information publications may be found in Quicklaw. Taylor cautioned against solely relying on the Ministry of Health guide My Voice: Expressing My Wishes for Future Health Care Treatment, which she indicated may be confusing to canadiaboth non-professionals and professionals.

— Gail Curry

What the WARC? Connecting researchers with web archive data presented by Nicholas Worby, Government Information & Statistics Librarian, University of Toronto.

Worby, Government Information and Statistics Librarian at the University of Toronto Libraries, gave an overview of his work with UTL’s government information focused web archiving projects underscoring that administrative changes can result in major changes to web site content and a “race against time” to capture the historical record. As well as participating in the Canada-wide academic library project of archiving federal government web sites, the UTL web archive includes Ontario provincial and Toronto municipal government web sites, U of T affiliated sites and local event based collections, such as the PanAm games, Toronto Mayoral election and the Umbrella Revolution

Worby described how web archiving works both to preserve data and to present it for access and use. The goal is to present these web sites as they originally appeared, complete with interactivity, like a “snapshot in time”. This labour intensive process includes:

- consultations with stakeholder and other institutions to select appropriate content and avoid duplication

- negotiation of permissions and copyright

- capture and storage of data

- integration of tools for access, discovery and analysis

- application of metadata

- ongoing qualify assurance and trouble-shooting activities

- meeting the need for researcher support: use agreements, outreach and education

- advocating for institutional support

Worby emphasized the crucial involvement of government information librarians in web archiving, as an extension of their traditional stewardship role, despite the cost in time and resources. As with other primary source collections, the true value of government web archives may not be known for years.

Throughout the presentation, Worby was generous with technical details and tips for publicizing and assessing the value of these collections, sharing stories of traditional and unanticipated researcher use cases, exploiting data and text mining to reveal surprising connections and patterns.

Nicholas Worby can be reached at [email protected]

— Sylvia Roberts

What do you mean you don’t have a copy? An attempt to document Government of Canada web content removed from open access presented by Amanda Wakaruk, Government Information Librarian and Acting Digital Repository Services Librarian, University of Alberta.

Amanda Wakaruk spoke to the gathering on the Government of Canada’s (GoC) “precarious publishing patterns” and shared stories of loss of government information. She first provided a review of changes and losses to GoC web content since 2000 resulting from the TBS Common Look and Feel standards, accessibility standards, ROT guidelines, library closures, and Web renewal plans. While there has been some web archiving by LAC and Archive.org (Wayback Machine) she indicated archiving is largely incomplete leading to gaps in the collection. Wakaruk went on to discuss a joint study she’s involved in at the UofA, the GoC Web Content Project and her own sub-project on GoC databases. She shared the results of her sub-project on GoC databases examining whether or not content from databases on three specific federal departments and agencies (Immigration and Refugee Board, Industry Canada, Health Canada) changed, or even still exist, between 2005 and 2014.

Using the DSP Supplementary Checklists for 2005 to 2008 along with InfoSource, (a key federal government database directory which is no longer maintained) Wakaruk wanted to determine if these federal databases still existed and to compare them with current (2015) open access databases. Tracing the denouement of the databases required using the original DSP supplementary Checklists, the originating departmental website, the Wayback Machine, LAC Amicus records, and open.canada.ca. Wakaruk determined there has been a drastic reduction in the number of databases and related content since 2005 for each of the targeted departments and agencies. Information is either not available or only partially available. Information that is only partially available might be found:

- In the WayBack machine, but with holes and dead links

- on a GoC website through mediated access;

- via a fee-based service; and in some cases, information has been sent off to another organization, i.e. commercial database provider or an international agency.

She concluded that web content losses are difficult to track. Access to database content is convoluted and may require mediated access. Fundamentally, the removal of unique database content is at odds with the concept of open government with the result that stewards (us) and creators (government) are at odds.

— Caron Rollins

GovInfo Day 2016 will be held on Friday, May 6, 2016.

Mary-Anne McDougall is the Information Services and Special Collections Librarian at the University of the Fraser Valley

Chris Burns is the Research Support & Data Services Librarian at Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Gail Curry is the Data, Map & Government Information Librarian at the University of Northern British Columbia

Sylvia Roberts is the Communication and Contemporary Arts Librarian at Simon Fraser University

Caron Rollins is the Librarian for Government Publications, Political Science, and European Studies at the University of Victoria

Carla Graebner is the Data Services, Government Information and Economics Librarian at Simon Fraser University

[1] Canada’s Action Plan on Open Government, 2014-2016. http://open.canada.ca/en/content/canadas-action-plan-open-government-2014-16

[2] Directive on Open Government. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=28108

At a minimum, the following information resources of business value are to be open by default and released, subject to valid exceptions, such as ownership, security, privacy, and confidentiality, as determined by the department. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will support departments in the development of their decision-making process to evaluate the legal and policy issues by providing a release criteria checklist and other guidance tools.

- All mandatory reporting documents (e.g. reports to Parliament, proactive disclosure reports); and

- All documents posted online or planned for publication via departmental web sites or print (e.g., statistical reports, educational videos, event photos, organizational charts).

From: Appendix B: Mandatory Release of Government Information: Open Information. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=28108#secB.2

[3] Listing of Government of Canada Organizations under the Financial Administration Act (FAA). http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/gov-gouv/tools-outils/org-eng.asp

[4] Definition of BagIt from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BagIt

[5] Representation Agreement Act (current to October 21, 2015). http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96405_01