September 15, 2015 marked the hundredth anniversary of the Legislative Library’s service in its current home: the stunning south wing of the British Columbia Parliament Buildings.

Humble beginnings

The Library itself was born before the confederation of the province, established by a small grant from the Colonial Legislature of Vancouver Island in 1863 (Barton, 1987). A few books were purchased and shelved unattended in a single room (“The British Columbia Legislative Library,” 2002). Statutes, parliamentary papers, and reference materials were added slowly over time, and when R.E. Gosnell was appointed the first Provincial Librarian in 1893, there were between two and three thousand items in the Library collection (Library Finest on Continent,” 1912). Gosnell had big ambitions for the Library – envisioning services and resources that could support not only the Legislative Assembly, but also the rest of the Province (Barton, 1987). He purchased as many works as possible to further his vision, and when the Parliament Buildings were completed in 1897, the Library moved into new quarters inside (“The British Columbia Legislative Library,” 2002). Thanks to Gosnell and his successor, E.O.S. Scholefield, the Library rapidly outgrew this space as well. Within six years, 18,000 volumes were spilling into nine rooms (“Report on the State,” 1934), and Legislature staff even considered converting the kitchen and dining room into additional Library space (ibid). When plans were made to build additions to the Parliament Buildings, it was clear that a new Library had to be included. Francis Rattenbury, architect of the original buildings, returned to design the expansion project in 1911 (Segger, 1979).

Building a new home

In September 1912 the Governor-General, His Royal Highness the Duke of Connaught, arrived in Victoria to lay the cornerstone for the Library wing. According to a local newspaper, the cornerstone included a time capsule of sorts – a leaden box containing, among other things: photographs of the Duke and Duchess, of the Lieutenant-Governor, and of the Premier; plans for the building; a 1911 Provincial Yearbook; a set of gold, silver and copper coins of the Dominion; a full set of stamps; and that morning’s newspapers from across British Columbia (“Library finest on Continent,” 1912). At the time, it was noted that the Duke had granted his name for the Library’s use, and the press spent great pomp and ceremony praising the future ‘Connaught Library’ (“Connaught Library Opened,” 1915). Sadly, the name did not stick much beyond that year and, in line with Gosnell’s vision, shortly became known as the ‘Provincial Library’ instead. It’s unknown whether or not this was a terrible disappointment for the Duke.

Construction of the expansion took three years, and by the summer of 1915, the Library began moving into its current home (“Report on the State,” 1934). Reports from that year indicate that the entire collection – tens of thousands of items – was moved by the small but enthusiastic Library staff (ibid). E.O.S. Scholefield, then the Provincial Librarian, noted that the task was completed so ‘cheerfully’ (“Annual Report”, 1916) that the move was finished in only a few weeks (“Connaught Library Opened,” 1915). The Library was able to open its beautiful new space to the public on September 15, 1915 (ibid).

The provincial library

The early Librarians’ ideal of creating a library that could serve the whole Province had a hand in forming library and archives services all over British Columbia. From almost the beginning, the Library curated a separate, smaller collection to focus on the history of British Columbia (Barton, 1987). Materials were painstakingly selected from all over the province for decades (“Report on the State,” 1934). These items became the bedrock of the Provincial Archives. For many years, the Provincial Librarian also received the title of ‘Provincial Archivist’ (Barton, 1987), and the archival collection was managed and stored by the Library. In 1970, the B.C. Archives separated from the Library and moved into a building of its own nearby (Library Development Commission, 1974).

Starting in 1898, the Library also maintained a travelling library program, which sent small collections of fifty books to anywhere in the Province that required it (“Report on the State,” 1934). This included smaller communities without library service, schools, lighthouses, even ships at sea (“The British Columbia Legislative Library,” 2002). When the Public Library Commission was established in 1919 they took over this service; by that point almost 200 travelling collections were in circulation (ibid).

In spite of managing these and other projects, the Library continued to provide important services to Legislative staff and members of the Assembly. This included everything from research and reference, to supplying publications and other materials, and eventually to technical and computer support.

The Reference Department itself has a history almost as long as the Library wing. It was established in 1920, and at the time was lauded as the first distinct Legislative Reference Department in Canada (“Report on the State,” 1934). The Department was created to “furnish the Ministers and their Deputies, Members of the Legislative Assembly, and the Legislative Counsel and other public officials such information as they require” (ibid). It continues with this mission today.

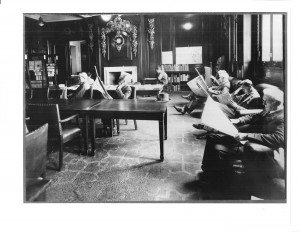

Photo of the Legislative Library of BC in Victoria, B.C., courtesy of Iona Reid, Acquisitions/Serials Librarian.

Photo of the Legislative Library of BC in Victoria, B.C., courtesy of Iona Reid, Acquisitions/Serials Librarian.

The legislative library

With the Archives separated and Public Library services long-since flourishing, during the 1970s the Library decided to re-focus and prioritize their services to members of the Legislative Assembly. They stopped using the ‘Provincial Library’ name and instead took up their statutory title: the ‘Legislative Library’ (Barton, 1987). Over the years, the Library has maintained a strong focus on Legislative services. However, true to its roots, a small amount of ‘Provincial Library’ services remain. When staff are not working to support the Legislative Assembly with research or materials, they find time to help public scholars, historians and press.

The Legislative Library has surpassed R.E. Gosnell’s dreams: a comprehensive collection that supports the political and the public, staffed by a long line of talented and passionate individuals. The Library staff are proud of the work they do for each and every client, and they look forward to the challenges brought on by the next hundred years.

Andrea Lee is a Research Librarian at the Legislative Library of BC in Victoria, B.C.

References

Annual Report 1915-16: Provincial Library and Provincial Archives of British Columbia. Victoria: Provincial Library and Archives, 1916.

Barton, Joan. “British Columbia’s Legislative Library: All Things to All People or Just a Schizophrenic Organization?” Victoria Forum. June 1987: 7.

The British Columbia Legislative Library: Shaped By Its Past. PowerPoint Presentation to APLIC/APBAC and Guests. Quebec City, September 24, 2002 [Speech Transcript]. Victoria: Legislative Library, 2002. http://intranet/library/intranet/llbcdoc/llbchistory/aplic_sep_02_no_pics.htm

“Connaught Library Opened to Public.” Victoria Daily Times [Victoria] 15 September 1915: 11.

Library Development Commission and British Columbia Legislative Library. A Proposal for Re-organization and Extension of Government Library Services in British Columbia. Victoria: Legislative Library, 1974. http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/pubdocs/bcdocs2011/470813/a%20proposal%20for%20reorganiztion%20of%20govt%20library.pdf

“Library Finest on Continent.” Daily Colonist. [Victoria] 28 September 1912: 1, 16.

Report on the State of the Library and Archives. Victoria: Provincial Library and Archives, 1934. http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/PubDocs/bcdocs/456244/State_of_the_Library_Archives.pdf

Segger, Martin. Ed. The British Columbia Parliament Buildings. Vancouver: Associated Resource Consultants, 1979: 10-13.