Across Canada, groups recognize the last week of September as Right to Know Week. During this time we acknowledge the importance of freedom of information (FOI) laws to society. This year is particularly important, because 2016 marks the 250th anniversary of the world’s first freedom of information law. On Dec. 2, 1766, Sweden became the first country to recognize that citizens had a right to access unpublished information.

The basic idea underlying most freedom of information legislation is easy to understand. They typically start by giving individuals a general right to access unpublished information held by most government or public bodies. While generally a good thing, such a sweeping right could cause harm in certain circumstances. As a result, FOI laws also define specific exceptions to this right where disclosure could actually harm other public interests. FOI laws therefore also define classes of information that public authorities are allowed to withhold. For example, British Columbia’s FOI law allows the government to withhold information about endangered species if disclosure would result in harm to those species.

A common sentiment is “Why do we need freedom of information legislation? The government should post everything online!” In 2014, the federal government announced a Directive on Open Government, which required datasets and certain types of reports to be “open by default.” This would seem to be a promising step towards putting everything online.

However, there is a reason to doubt that everything could be posted online and replace robust freedom of information legislation. Before the government can publish anything, it must be reviewed to ensure confidential information is not inadvertently disclosed. According to the federal Directive on Open Government, information can only be made available only if “valid exceptions, such as ownership, security, privacy, and confidentiality, as determined by the department” do not apply. This means the information must be filtered before it goes online.

Filtering information is not a trivial process. It often requires consultations within government to determine if something meets the legal requirements for protection. It would be waste of resources to review every email, draft document, or datasheet held by public institutions.

Governments must ultimately decide to publish some things and withhold others. Unfortunately, when given this choice, they will choose whatever serves their political interests. Withholding materials from the public is a form of censorship that can only be minimized through robust freedom of information legislation.

Origins of freedom of information in preventing censorship

Looking to the past, it is clear that freedom of information legislation has its origins in censorship and freedom of the press. In 1766, Sweden’s parliament was debating whether to abolish the office of the censor of the Swedish realm. At that point, printing was subject to approval by an official censor. Swedish parliamentarians ultimately decided to abolish censorship, but a unique feature of the law they adopted was that it also allowed the public to access documents held by the state.

It is easier to appreciate the relationship between censorship, freedom of the press, and freedom of information legislation if we imagine every public institution as having its own printing press. Each of these imaginary presses makes copies of material held by their institution available for any member of the public. An individual simply tells the printing staff what documents they would like, the printing staff then finds the materials, redacts sensitive information as required by law, and makes copies for the individual.

However, just as state officials have historically tried to control private sector presses, so too have they tried to control these public sector presses. While freedom of the press laws prevent governments from censoring private presses, freedom of information laws prevent them from censoring these public presses. Of course, these public presses are allowed to withhold information if legislation requires it to be protected. But if not, then there is no legal basis to stop these public presses.

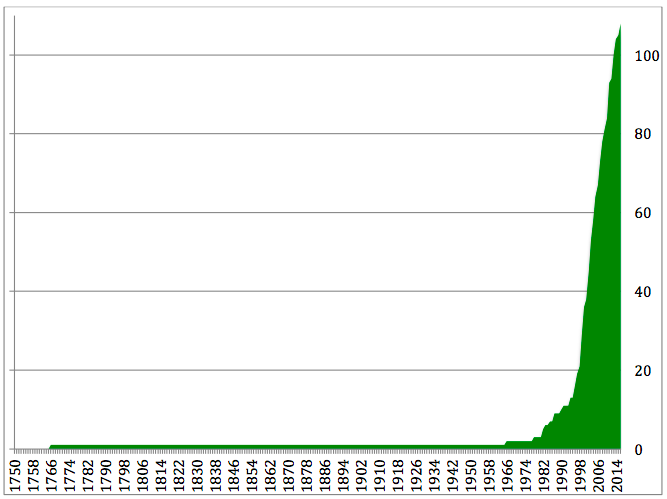

A surprising fact about freedom of information legislation is how slow the world has been to follow Sweden’s example. According to FreedomInfo.org, a network for FOI advocates based in the Gelman Library at George Washington University, the United States became the second country to adopt freedom of information legislation two hundred years after Sweden. Since then, countries have adopted FOI laws at a startling rate.

British Columbia’s FOIPOP Act

When BC introduced the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FOIPPA) in 1992, the goal was to have “the best freedom of information legislation in Canada” (Jones, 1992). Until recently, BC actually had a basis to say the goal was achieved. According to a rating by the Centre for Law and Democracy, BC’s FOI law ranks second highest amongst Canadian provinces and territories. Newfoundland and Labrador FOI law surpassed BC’s after its law was reformed in 2015.

Using your access rights in BC is relatively easy. Unlike other provinces, BC’s FOIPPA does not have a formal application process. There is no application fee, and, according to the FOIPPA Policy and Procedure Manual, “an applicant is not required to refer to the Act in the request.” An email seeking documents sent to a public institution subject to the Act should be sufficient to invoke your access rights.

A common question people have is “What information does that government have?” Initially, FOIPPA required the BC government to publish a directory to help people identity and locate information. The directory was comprised of:

- a description of the mandate and functions of each public body and its components,

- a description and list of the records in the custody or under the control of each public body,

- a subject index, and

- the name, title, business address, and business telephone number of the head of the public body.

The government was to distribute copies of this directory to “to public bodies and to public libraries and other prescribed libraries in British Columbia.” Although this section was eventually repealed, these original directories are still held by some public and university libraries in BC.

Reinstating this clause would likely be very helpful to British Columbians wanting to use their access rights. As librarians and information professionals know, the ability to browse descriptions of information resources is helpful because it allows people to recognize what information is relevant to them.

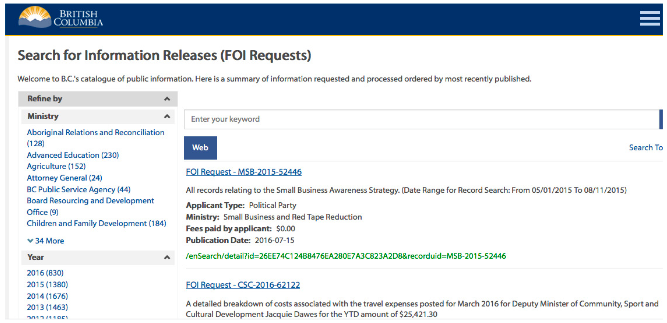

An interesting initiative of the BC government can be found on openinfo.gov.bc.ca. The site contains a feature that allows people to search and browse for documents released under FOIPPA as well as download the documents that were provided. Librarians will notice how this resembles a full-text, abstracting, and indexing database.

The database currently contains 6,690 sets of documents released through FOIPPA between 2011 and 2015. Reviewing the documents on openinfo.gov.bc.ca gives one a chance to reflect on the relationship between freedom of information legislation and censorship. Without a robust FOI law, the provincial government would have had no requirement to make any of this vast collection of documents available to the public.

Concluding thought

The 250th anniversary of freedom of information legislation is a major milestone in our global community. The occasion naturally invites for longer reflection and deeper thought. As Right to Know Week approaches this September, one thing to consider is that freedom of information legislation may ultimately be about the freedom to read.

Mark Weiler is the Web and User Experience Librarian at Wilfrid Laurier University. Mark recently gave testimony to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy, and Ethics. He completed his PhD from Simon Fraser University and served on the Board of Directors for the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association.

References

Jones, Barry (1992). Memorandum from Barry Jones, MLA to the Honourable Colin Gabelmann, Attorney General.

Freedominfo.org (2016). Chronological and Alphabetical lists of countries with FOI regimes. Retrieved on July 17, 2016 from http://www.freedominfo.org/?p=18223.

Test