This article examines a series of pilot reports developed with the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Toolkit. The toolkit was created by NORDIK research institute in partnership with Northern Ontario Libraries, and the reports were compiled between late 2016 and 2019. I feel that the reports are significant as they represent one of the first attempts to calculate the social as well as economic benefits that libraries provide communities, and also introduces an excellent framework for understanding library value. The seven pilot reports are an exciting first step towards an approach that I think has a lot of potential to help libraries justify their funding and make evidence-based decisions about library services and strategic direction in the future.

The idea of SROI fits into the major trend of evaluation and assessment in public libraries: moving away from counting outputs (books lent, program attendance) and toward outcomes (knowledge gained from books lent, skills learned from programs attended). Ultimately, the goal of comparable, more well-known evaluation and assessment initiatives like the Public Library Association’s Project Outcome, Logic Models, or the Institute of Museum and Library Services’ Measures that Matter is to assess the impact—the positive change on patrons’ lives and the community as a whole—that results from library initiatives and services. Library service is constantly evolving. As libraries choose which programs and services they should adopt, it would be helpful to be able to weigh the benefits that the community could expect to receive from each.

By and large, public libraries are already doing this in a qualitative way. That is, they strategically plan to ensure that their programming, service delivery, and new offerings match their mission and vision for the community. Often, they’re even harmonizing the library’s vision with their municipality’s broader vision. Where it gets tougher is when the library wants to pursue new and promising initiatives; existing programs and services might already match the mission and vision, so how can the library justify cutting an existing program? The easy answer is to cut those that are costing the most money and providing the least benefit. The trickier follow-up question is: how do we measure this benefit? How can we compare the benefits of two very different kinds of library service?

This requires being able to consider the impacts of different programs and services in a one-to-one way. Once we can do that, we can be more confident that we’re not missing out on opportunities to help people, or holding on to things that sound good but are no longer actually helping. The idea of converting the impact of libraries into monetary terms may seem misguided, given that it reinforces capitalistic structures that, in some sense, the library stands against. But management often works in dollar amounts when they decide how to allocate library funds. And for municipal libraries, the same is true of city officials who have to decide between funding the library and other worthwhile city departments. Given this environment, trying to quantify library impact can make a lot of sense.

Calculating Return On Investment (ROI) is one way to turn library impact into numbers. ROI is a business concept that captures the impact (in financial terms) of funding the enterprise, and while it has been applied to public libraries, it’s generally done in one-off studies, not on a yearly basis. Toronto Public Library, for instance, did an ROI study in 2013 and found that Torontonians receive $5.63 for every dollar spent on the library. This covers what economists call “tangible benefits.” Tangible benefits to a patron are the money they would have to spend if they wanted to replace the services they use at the library on the private market. (ROI also covers the stimulus to Toronto’s economy from funding the library, and re-spending in the local economy by the library and its employees, but those don’t concern us here.)

For-profit businesses use ROI with one goal in mind: to maximize the money brought back to the business. But benefit to libraries and other non-profits is quite different from benefit to a for-profit business. It’s not about dollars brought back to the institution, but about value delivered to patrons. Especially nowadays, libraries are much more than passive repositories of information; they are active community hubs, responsive to community needs, striving to welcome users with diverse needs and abilities. Their impact is primarily social, which is why this Northern Ontario Libraries’ SROI pilot project is so exciting. It’s one of the very first attempts in the public library sector to quantify, in dollars, their impact on communities while including the social impacts that may get left out of traditional ROI calculations. And these social impacts appear substantial: where TPL’s ROI study found $5.63 for every dollar spent, the SROI pilot reports found between $12 and $56 in value for every dollar spent.

In order to measure value to the community across multiple library systems, you need a model to organize the different ways that libraries actually provide value. The researchers for the SROI project, in consultation with the pilot libraries, developed an original and useful framework. This is especially apparent when comparing their model with the model underlying the better-known Project Outcome. Conceiving of libraries are community hubs, they identify seven areas where libraries contribute to building capacity at the individual, organizational and community level. Comparing these with the seven key library service areas used in Project Outcome, both include community engagement, literacy, and economic development. Project Outcome supplements these last two categories with summer reading and job skills, while also curiously dividing ‘lifelong’ and ‘digital’ learning into separate areas. While these divisions may mirror organizational divisions within libraries, in my opinion they omit additional areas of benefit that are present in the SROI framework, such as entertainment, social inclusion, and health and wellness. The SROI framework also includes cultural integrity and regional identity, an interesting area that may apply more to rural libraries (where communities have fewer competing cultural institutions) than to those in large cities. But, overall I think the framework developed in this study seems to do a better job capturing the breadth of public libraries’ impact on their communities than the Project Outcome model.

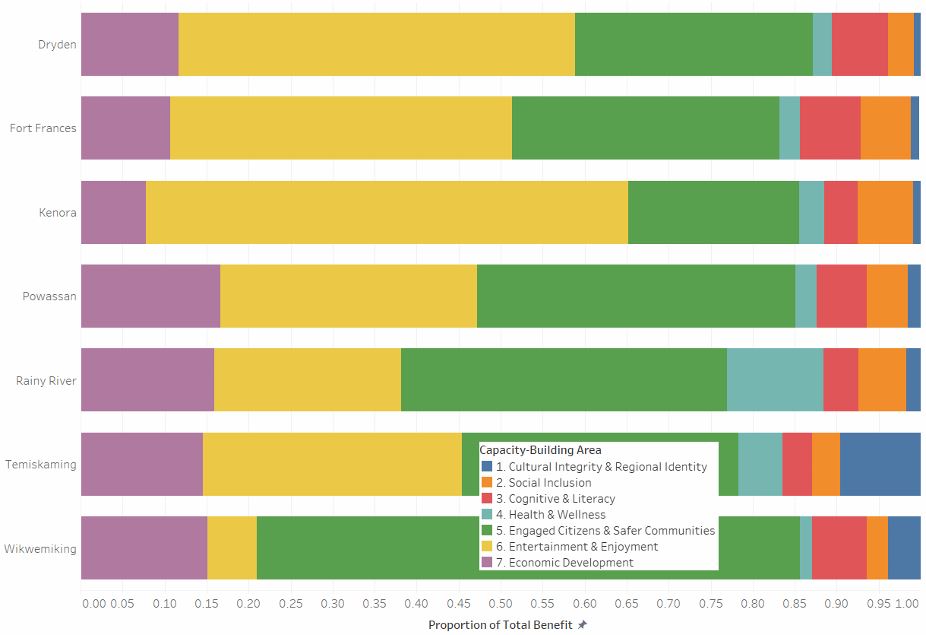

Fig.1. Proportion of Total Benefit for each pilot library by Capacity-Building Area.

With the framework in place, the next step in calculating SROI is to plug library statistics into a series of formulas known as indicators. Some assessment models use a large number of indicators and have individual institutions choose those relevant to them, but this pilot study worked with a standard set of 21 indicators (3 per area). Health and wellness, for instance, was assessed using the value of health-related programming, collections, and in-library requests. The calculations in this study were designed to use statistics libraries already collect in either annual or typical week survey data. This makes calculating SROI as easy as throwing some numbers your library system already has into an Excel sheet.

The downside to this simplicity is that the accuracy of the results depends on the quality of the assumptions made in the formulas. For example, in this study, the benefit to a patron attending a parenting workshop at the library is assumed to be $25, a generic “cost of program” that comes from the average ticket price to attend a cultural program outside of the library, which the researchers argue is therefore the “market rate” that patrons would be paying elsewhere. Similarly, the calculations also assume a $25 “cost of service” for answering any reader’s advisory, reference, or IT question, and that the benefit of a library membership is equivalent to the $483 average cost of an annual recreation pass (http://fopl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2019-Rainy-River-SROI-1.pdf). None of these numbers are outlandish, as they are similar to those used in TPL’s ROI study. Ideally, still, all of these amounts would represent the true benefit received by patrons, backed up by careful research. However, the reality is that we are largely still waiting on the foundational research to be able to do a good job of many of these calculations.

For library programming, at least, the foundational research is underway: an eight-year research plan from the ALA (in partnership with social science think tank Knology) is currently exploring the impact of library programming. With just phase 1 of the ALA project finished so far, it’s clear that there is substantial work involved in determining accurate benefit values for aspects of library operations. Similarly, the text of the SROI pilot reports do a great job of listing existing library programs and services that fit the framework areas, but because the research isn’t there yet to accurately estimate their impact, many of them don’t actually make it into the study’s calculations. As the assumptions that go into the calculations get more accurate and comprehensive, so will the results.

The real result of these pilot reports is the creation of the Valuing Northern Libraries Toolkit, which enables any library to create a report calculating their Social Return On Investment. As mentioned above, although the toolkit was developed in consultation with a specific set of Ontario libraries, it works for any library system. And as it only requires stats that public libraries in BC already collect (or have access to via their ILS), it’s a low-barrier way to introduce the concept of SROI to a library system, whether as part of a logical argument for funding, a way for staff to see the impact of their work, or to compare a library’s performance to other systems using the toolkit. And the results really do lend themselves to advocacy: benefit delivered per resident, per hour open, or per dollar of funding received are all easily grasped, powerful reminders of the continued relevance of libraries.

Fig.2. Main Findings from the SROI Pilot Reports by Library System.

The Valuing Northern Libraries Toolkit is a good way to introduce the SROI concept, but at this point in its evolution it’s not as rigorous as its quantitative nature would suggest. The large difference in impact found among the study’s pilot libraries ($12 to $56 per dollar spent) speaks as much to the preliminary nature of the findings as to the diversity of the libraries studied. What’s clear is that these results are higher than those found in traditional ROI studies, and that seems to be due to the inclusion of previously uncounted social benefits. But to be truly unassailable as an argument for funding, and especially as a tool to guide library resource allocation, the results need to be supported by more research than currently exists. Still, since the broader trend in evaluation and assessment is toward investigating outcomes and impacts, I believe that the SROI approach and framework is already valuable and will continue to become more accurate and useful over time, as assumptions improve and as evaluation and assessment initiatives like Project Outcome start to convince libraries to collect more patron impact data. For now, the Toolkit is an approachable way to emphasize, with numbers, the vital social role that we already know public libraries play in our communities.

Greg McLeod is a recent MLIS grad and auxiliary librarian at Burnaby library. He’s interested in using data to explore the intended and unintended consequences of library policies and practices.